How to Read a Recipe: “Christmas Cake” aka “Advent Cake” aka “Coffee Cake” aka “Pfefferkuchen auf dem Blech”

Hello everyone! Before diving into today’s topic, I’d like to take a moment to recap the theory and examples shared in past posts that will help us with today’s close reading of a traditional recipe.

In “Family Cookbooks: Stories Worth Reading,” I talked about the ways in which personal cookbooks can be read to understand a person’s identity. In that post, we looked at a family cookbook I made for my cousin’s wedding to show that family cookbooks offer important clues about family dynamics.

In “I speak food – and so do you,” I shared some of the theory that has influenced food scholars to determine that food is like a language and that food-languages “structure social behaviour and… affirm one’s beliefs and values to one’s self and others.” In that post, as in my PhD dissertation, I insisted that though food can be studied from a structuralist perspective, I align my work with those who argue that we need to understand the larger context in which that food exists if we are to understand what is actually being said when someone desires, requests, makes, and/or serves specific items.

Finally, in “Peach Pie and Pie Crusts – How Food Creates Identity,” I looked at the power traditional foods have in forging cultural identity. As in “Family Cookbooks: Stories Worth Reading,” this post touched on the ways in which recipes fall into categories of inclusion and exclusion, or integration and differentiation plots to use Anne Bower’s terms. We looked at peach pie specifically, and the generic pie crust, as examples of how food items that include or differentiate people within a specific place.

Today, I wanted to show how individual recipes can be mined for biographical information. Using three versions of the cake I wrote about in “Decoy Food and Christmas Magic: The Deceptive Power of Pfefferkuchen auf dem Blech,” today’s post aims to give you strategies for analysing your own favourite and treasured recipes.

Step 1: Look at the recipe and record your first impressions.

Questions you can ask yourself: Where does the recipe come from? Is it in a book or handwritten? What language is it written in? What annotations have been made to it? In whose hand? What is the nature of those annotations? How used is the recipe?

Exhibit A:

Here is a picture from my Oma’s Dr. Oetker baking cookbook. You can see that it is in German, that it is well used, and that Oma has made a few minor amendments to it – notably in the amount of sugar she puts in it and the baking dish she uses. You can see that her annotations are in German.

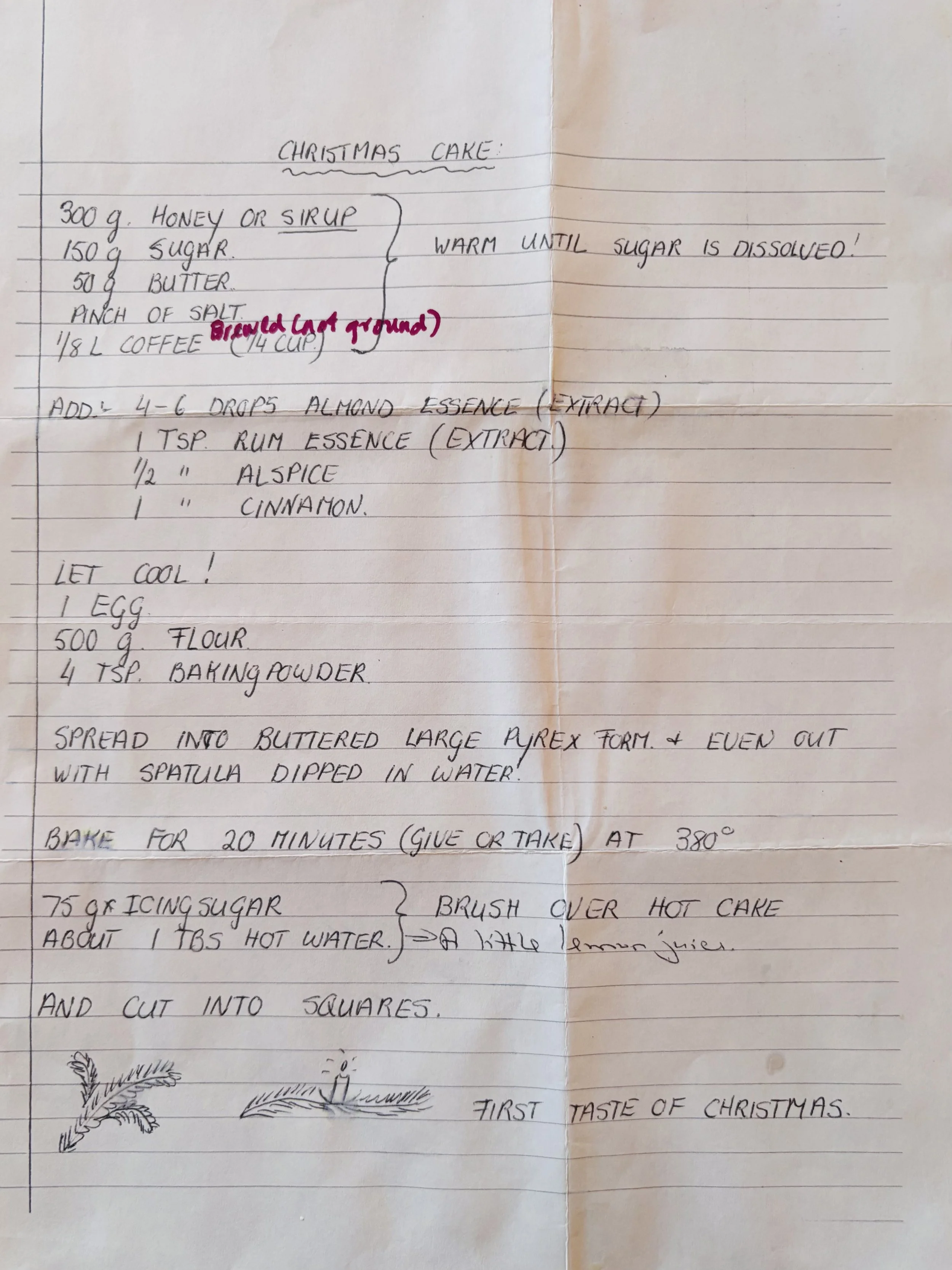

Exhibit B:

This second picture comes from my mother’s recipe box. It’s the version my Oma translated from her German cookbook for my non-German speaking mother. The title of the recipe is now “Christmas Cake” rather than the long, complicated German version. Oma’s modifications are still present in this version: the use of a Pyrex pan, and the changes to the amount of sugar. For those of you who can read German, you’ll notice that Oma has made other small changes in her translation. My mother’s version is also stained and worn. My mother has also left minor traces on her version by adding lemon juice to the icing. She’s also quantified that amount of lemon juice and reduced the amount of flour. Two notes her recipe has that my version doesn’t. You’ll also notice the note about the coffee being instant coffee - a note she added after my disasterous first attempt at making this recipe.

Exhibit C:

This is my version of the recipe and the one I used a few weeks ago when I wrote my last post. You can see that I am using the translated version, not a copy of Oma’s version even though I do speak enough German to get by with the original. My version includes my mother’s addition of lemon juice to the icing. I have also left notes to help me understand that one should not put straight up ground coffee into the batter. My copy shows little evidence of use.

Step 2: Look for biographical clues in the handwritten notes and determine the facts these notes share.

Questions you can ask: Who made changes to the recipe? What changes did that person make? What language are these changes written in? How is the writing organized? What other marks or traces did the person leave on the recipe?

Oma

The Exhibit A version shows us that Oma speaks German, likes a Pyrex baking dish, and that she cuts sugar where she can. Exhibit B also tells us important information about her: she organizes her writing into what a recipe normally looks like, she likes to make things pretty with creative embellishments, and Christmas matters to her. All this is evident in the way she’s underlined the title, organized the ingredients and instructions into sections, and included drawings at the bottom of the page. When looking at handwritten recipes, we can gather important clues about language in the words that are used. In Exhibit B and C, for example, Oma’s German roots come out when she writes “SIROP” instead of “SYROP.” It’s a small typo, but one that is telling of her linguistic background.

We see that Oma considers this cake to be the “FIRST TASTE OF CHRISTMAS” and her drawing of the Advent wreath with the candle and the greenery of the season further associate this recipe with Advent, the four weeks before Christmas. Both the words and the images are important elements to understanding when Oma makes this cake, and what traditions matter to her. We cannot gather from this recipe whether or not she makes the cake at other times of the year, but it is evident that this is one she associates with the holidays. We can also see that it is one that is made often, one that matters.

My Mother

Though we learn less about my mother, we see that she does prefer a tarter icing in that she adds lemon juice to hers. We can see that she evidently likes this recipe as she’s made it often enough for it to be stained. What is particularly interesting is the fact that she’s recently made changes to the recipe. Some of these, such as the note about the coffee, comes from our conversations over the past few weeks. The other changes as well as the fact that she’s rewritten some of the letters that have disappeared over time, show us that she makes this cake often enough to care about the ingredients that will make a successful cake.

Me

About me, we learn that I don’t drink instant coffee and need to be reminded that I need to used brewed coffee rather than ground. (Yes, I really put a ¼ cup of ground coffee in my first attempt at this cake. Epic fail.) I don’t drink instant coffee, so the thought of using it never even entered my mind. This tells me that I prefer brewed coffee. That I haven’t included a specific measurement for the lemon juice suggests that I understand what a “little” means.

Step 3: Analysis

Questions you can ask: How does the recipe’s evolution show shifting family dynamics or realities? In what ways does the recipe include others? In what ways does it exclude others? What does the recipe tell me about what matters to the person making it? Is there a cultural, historical, contextual, or other type of clue present in the written recipe or the annotations that can tell me about the real lives of the people making this food? What do I know about the person? What do these changes tell me about the person? How is the recipe passed down (orally, in writing, via transcription, through another copy of the book…)?

*Though these questions can give us direction, we need to be weary of making assumptions. Always approach recipe reading with a curious mindframe, ask questions of the people who are making it when you can, and acknowledge your bias when you recognize it.

Cultural Analysis

This recipe is clearly tied with my family’s German roots. Exhibit A coming from one version of the iconic Dr. Oetker baking cookbook. According to their website, Dr. Oetker has been publishing recipe books in various forms since 1891 and they claim that “[t]here is hardly a household in Germany in which a Dr. Oetker recipe booklet or cookbook and baking book cannot be found.” This statement is certainly true of these three women. Oma brought her Dr. Oetker cookbook with her when she moved to Canada from Namibia, a former Germany colony and she gifted my mother her copy as a wedding shower present.

My two Dr. Oetker cookbooks were also presents. The Dr. Oetker Best Recipes German Cooking and Baking came, I think, from my aunt Ingrid, who, I seem to remember, wanted me to have a book of German recipes. As the only one of my siblings interested in learning the language and as my godmother, this was a logical gift for her to give me. The German home baking version comes from my mother who gave it to me as a present when I was doing my PhD on traditional food. She thought it was important for me to have a copy of the recipes I was writing about and my own version of the book and the recipes often talked about.

The way these books made their way in our homes is worth is small digression from our reading of today’s recipe. Oma brought her version of the book with her from Namibia. For her, it was important to bring the recipes from home with her into her new life in a new country. For my mother, the book was a way to welcome her into the family she was entering. It may also have been a way for Oma to share with her the recipes my father grew up with and would maybe be reminiscing about and asking for. My cookbooks are a way for the generation of women before me, both German and non-German, to offered me a piece of my cultural heritage.

Significantly, the recipe for “Pfefferkuchen auf dem Blech” is only in Oma’s version of the Dr. Oetker cookbook. It does not show up in my mother’s or mine and from the investigation I’ve done into this recipe over the past month, I’ve learnt that it’s not in my aunt’s book either. There are lots of versions of it online, but its absence means that if the generations after Oma want to make this particular, iconic German food, as authentically like Oma’s version as possible, they have to rely on her, the holder of the original recipe, to pass it on. What has happened over the past weeks has been an important coming together of Weiskopf family minds. As I’ve asked my cousins, mother, Oma, and aunt about it, we’ve shared stories about the cake, realised how important our paper copies of it is, and determined personal culinary preferences. This networking and sharing has further bound us to each other, affirming not only our own individual ties with German culture, but with each other as a family.

It would be easy to assume that the gifting of this recipe is a way for one generation to insist on foods that must be made. Scholars have looked at the implications of recipe sharing as a didactic tool for shaping new members of a family members. This recipe is a good reminder to check assumptions. It would be easy to assume that my mom was given this recipe to teach her how to be a good, German wife. But that’s not necessarily the case. My mother received this recipe when she asked for it. I also received this recipe when I asked for it. Now perhaps one could argue that Oma thought it was in the recipe book she gave my mom and that my aunt and mother also thought the same, but the fact that we have and use Oma’s handwritten copy rather than the books ultimately shows that we rely on Oma’s words, not the official, printed version and that lessons about what constitues good food comes as much from the person making the food as the parent. If the younger person doesn’t care about the food and/or if no one wants it or even knows to ask for it, then foods easily disappear. Lessons about “good” food can easily fall on deaf ears and hands busy with other priorities.

One last cultural point about this recipe that I gathered from my research is related to the larger cultural context with which this recipe is associated. Oma, as we saw in the last post, made this cake at the beginning of Advent and to cover the smell of the Saint Nicholas cookies she was making. My cousins remember eating this cake as part of the Advent ritual that took place at Oma and Opa’s. They would like the candles on the Advent wreath and sing Advent songs like “Alle Jahre Wieder” and “Leise Reselt der Schnee.” When they came to Canada and settled in Callander, Oma and Opa did not join a church, yet they came from families that celebrated this religious holiday and so maintained this tradition.

My cousins’ memories are not my own. I can vaguely remember lighting one of the Advent candles one time at Oma and Opa’s, but we weren’t there regularly during Advent, at least not from an age I can remember. My siblings and I celebrated Advent at mass and at school, not in our home. I have no memories of my father being involved in any of these Catholic rituals and any religious observance came from the French-Canadian side of my family. So why do my cousins remember the traditional lighting of the candle, singing of the songs, and eating of the cake? Why were they there but not us? This might be related to the fact that they lived out of town and would have stayed at Oma and Opa’s during the holiday season while we didn’t. It could be that their own mothers continued the tradition or insisted on being there for it, but my father didn’t care enough or was too busy to make it a priority. I could be an example of the role mothers play in passing on traditions.

This analysis shows us that though traditions often pass from mother to child, it doesn’t mean that daughters-in-law who come from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds can’t take the reins when the sons don’t. It also shows that even if one doesn’t grow up participating in a all of the cultural practices associated with a holiday, it doesn’t mean that we can’t participate in others. The food signals the allegiance to culture and cultural practices, even when these change over time.

Analysis of Family Dynamics

Scholars also look at recipes to understand shifting family dynamics. Recipes, as mentioned above, can sometimes be forced on newcomers. They can be accepted or rejected by them as well. In the case of this recipe, we know that my mother and I asked to have this recipe and so it was not an imposition, but rather a genuine desire to eat a dessert we enjoy and we want to share this good food with others.

Importantly, we see that Oma wanted my mother to succeed in making the cake. She writes out that the almond and rum “ESSENCE” may also be known as “EXTRACT” to help my mother with what may be unfamiliar ingredients. The exclamation mark after the “LET COOL!” is a great example of her ability to insist on the important part of the recipe that she may have explained orally, but wouldn’t have bothered to write out on paper. (If one doesn’t let the syrup cool enough, the egg will cook upon hitting it. One needs to let the mixture cool for the egg to integrate properly.)

Her explanations that the cake needs to be evened out “WITH SPATULA DIPPED IN WATER” is also super helpful since this is a gooey, sticky dough that clings to everything, especially the wooden spoons Oma always uses for baking. (To be honest, my silicon spatula didn’t need the water, but I did end up with a very textured top to my cake. Having dipped the spatula in water would have allowed for a smooth surface.)

Finally, her explanation that the icing be placed on the “HOT” cake distinguishes this from other cakes that would see the icing put on once the cake is cold and does signal to my mother, who may have been more familiar with traditional cakes, that this cake is different.

What we also see with this translation is that this German family is changing. My father always spoke German at home. My cousins learnt German from their mothers. But in our mixed-language and mixed-cultural home, we French was our first language. My father never spoke German to us. Thus, this recipe shows us that the family’s linguistic reality has changed. That I use the English rather than the German version of this recipe means that despite its German roots, it now exists in a translated, English version and likely will for generations to come. My kids don’t speak German and don’t care to either. So even if I went back to the German original, I would have to translate it for them. Maybe my cousins’ versions are in German and those will go on in German with their own children, but, for our branch of the family, it won’t.

The linguistic assimilation toward English is a subject that has been written about a lot, but here we see evidence of it. Assimilation connotes negotiation of all sorts of cultural elements, and food is no exception. There are lots of German foods my dad grew up with that my mother doesn’t make, but there are many that she does. Here is an example of a food that has been kept, and of people, practices, and values that are remembered and shared.

Step 5: Next steps

As you can see, a lot can be gleaned from a recipe. All of these little lines, small as they may seem, are important pieces of a story of who a person is, what makes a family, and how food serves to create community. There are a lot of personal details in these handwritten artifacts.

When we pull our recipes out, when we see evidence of the people who have handed these traditions down to us, we participate in keeping them present in our lives. Thus even if we may lose a piece of the history by writing recipes down, it’s important that we do and that we share them with the next generations. When we make food the actions, the sounds, the smells, the tastes, all combine to make the past tangible parts of our lives. We talk about the recipes and discuss the notes on the page that make those who handed them down to us real people who have shaped and influenced us.

Interested in reading more academics texts that study the ways in which recipes tell us about the people writing and making them? Here our some suggestions to sate your intellectual needs!

Check out the many essays in Recipes for Reading Community Cookbooks, Stories, Histories edited by Anne Bower (especially ““Bound Together: Recipes, Lives, Stories, and Reading: Introduction” by Anne Bower and “Claiming a Piece of the Pie: How the Language of Recipes Defines Community” by Colleen Cotter.

Acquired Taste: Why Families Eat the Way They Do edited by Brenda L. Beagan, Gwen E. Chapman, Josée Johnston, Deborah McPhail, Elaine M. Power and Helen Vallianatos.

Vincent Agro’s In Grace’s Kitchen: Memoires and Recipes from an Italian-Canadian Childhood.

The many essays in Edible Histories, Cultural Politics: Towards a Canadian Food History, Edited by Franca Iacovetta, Valerie J. Korinek, Marlene Epp (especially “More than ‘Just’ Recipes: Mennonite Cookbooks in Mid-Twentieth-Century North America” by Marlene Epp and “Gefilte Fish and Roast Duck with Orange Slices: A Treasure for My Daughter and the Creation of a Jewish Cultural Orthodoxy in Postwar Montreal” by Andrea Eidinger).

Edible Ideologies: Representing Food & Meaning edited by Kathleen LeBesco and Peter Naccrato

The “Introduction” of Cultural Studies by Cary Nelson, Paul A. Treichler, and Lawrence Grossberg.

David Sutton’s Remembrance of Repasts: An Anthropology of Food and Memory.

Janet Theophano’s Eat My Words: Reading Women’s Lives through the Cookbooks They Wrote.

Diane Tye’s Baking as Biography: A Life Story in Receipes.

Janice Wong’s Chow: From China to Canada: Memories of Food + Family

I’d love to hear about your recipe reading adventures! You can share your stories with me on Instagram @FranglischFoods or via email at franglischfoods@hotmail.com!

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Please read my Disclaimer page.